|

|||||||||||||||

|

CLICK ON weeks 0 - 40 and follow along every 2 weeks of fetal development

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

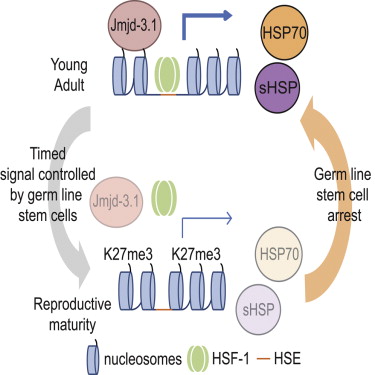

A genetic switch starts the aging process by turning off the cell's ability to respond to stress. Responding to stress would otherwise protect a cell by keeping essential proteins folded as well as functioning. The switch is thrown by germline [sperm and egg] stem cells in early adulthood, after reproduction begins. While the studies were conducted in worms, the genetic switch and other components identified by scientists as part of aging, are conserved in all animals — including humans. And as C. elegans has a biochemical environment similar to our own, it is a popular animal model for human disease and for human aging. Knowing more about how the quality control system works in cells could help researchers unravel how cells are capable of providing their own "quality of life" and may help us delay those diseases related to aging.

The study, built on a decade of research, is published in the journal Molecular Cell. Johnathan Labbadia PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in Morimoto's lab and first author of the paper. Almost all individuals of C. elegans are female hermaphrodites, with a small minority, around one in a thousand, being true males. They have an average lifespan of around 2–3 weeks, and begin to decline eight hours into their adulthood. Richard Morimoto and Johnathan Labbadia's work has identified that the animal's germline stem cells control when cell switches get thrown to shut down all of an animal's protective mechanisms against cell stress. In all animals, including humans, the heat shock response is essential for keeping proteins correctly folded thus protecting cell health. Aging is a decline in that quality control, which is why Morimoto and Labbadia specifically targeted heat shock response for study.

"C. elegans has shown us that aging is not a continuum of various events, which a lot of people thought," Morimoto explains. "In a system where we can actually do the experiments, we discovered a switch that is very precise for aging," he added. "All these stress pathways that insure robustness of tissue function are essential for life, so it was unexpected that a genetic switch is literally thrown eight hours into adulthood, leading to the simultaneous repression of the heat shock response and other cell stress responses." Using genetic and biochemical approaches, Morimoto and Labbadia found the protective heat shock response declines steeply over a four-hour period in early worm adulthood, precisely at the onset of their reproductive maturity. The animals appear normal in behavior, but scientists can see molecular changes indicating the decline of protein quality control.

Morimoto: "This was fascinating to see. We had, in a sense, a super stress-resistant animal that is robust against all kinds of cell stress and protein damage. This genetic switch gives us a target for future research." Abstract Highlights

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||