|

|||||||||||||||

|

CLICK ON weeks 0 - 40 and follow along every 2 weeks of fetal development

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

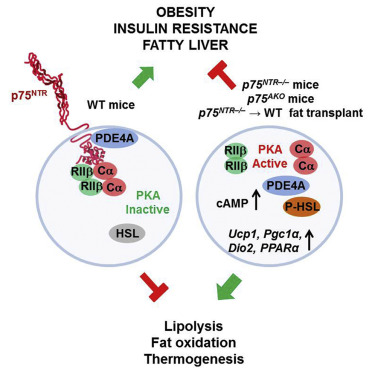

Brain receptor regulates fat burning in cells Scientists at the Gladstone Institutes — an independent and nonprofit biomedical research organization affiliated with the University of California at San Francisco — have discovered an unusual regulator of body weight. Interestingly, it was found in a mechanism commonly associated with brain cells. After lowering levels of p75 a NeuroTrophin Receptor (NTR) involved in neuron growth and survival, it was found mice being fed a high-fat diet were protected from developing obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver disease. In addition to its role in the brain, p75 NTR is also in the liver and fat cells and elsewhere throughout the body. Previous research has implicated p75 NTR in liver disease and insulin resistance, both consequences of metabolic syndrome and obesity. In the current study, published in Cell Reports, the relationship between p75 NTR and a high fat diet was examined more deeply, which is when scientists discovered it helped regulate metabolic processes controlling weight. Reducing the level of p75 NTR in fat cells prevented weight gain in mice. "We've identified a novel molecular mechanism that regulates energy expenditure and may help prevent obesity and the metabolic syndrome," says lead author Bernat Baez-Raja, PhD, a research scientist in the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease. "The complete protection from obesity and metabolic dysfunction in the study animals, without any differences in appetite or physical activity, suggests that p75 NTR is a key regulator of fat burning." Researchers experimentally removed p75 NTR from mice — and then fed them a high-fat diet. Remarkably, the mice resisted weight gain and remained healthy and lean after several weeks on the rich diet. On the opposite spectrum, normal or "wildtype (WT)" mice fed the same diet became obese, had larger fat cells, higher insulin levels, and developed signs of fatty liver disease — even though there was no difference between the diet of wildtype and p75 NTR-depleted mice, overall energy consumption, or physical activity. Rather, experimental mice had significantly greater energy expenditure than the wildtype mice, most likely because they burned more fat.

In a final set of experiments, investigators found that in particular p75 NTR's role in fat cells contributed significantly to regulating body weight. Deleting p75 NTR only from fat cells produced similar outcomes as deleting those same receptors from all cell types. What's more, transplanting fat cells from experimental mice into wildtype mice protected the wildtype mice from developing obesity. The next step is to develop small molecules or drugs to regulate p75 NTR in order to reproduce this effect and potentially serve as an intervention for obesity and metabolic syndrome. Abstract Highlights Other Gladstone scientists on the study were Eirini Vagena, Dimitrios Davalos, Natacha Le Moan, Jae Kyu Ryu, and Justin Chan. Researchers from the University of California, San Diego, the University of Glasgow, and King's College London also took part in the research. Funding was provided by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the UCSF Liver Center, the UCSF Diabetes and Endocrinology Center, the Spanish Research Foundation, and the Medical Research Council. About the Gladstone Institutes |

Jan 25, 2016 Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News News Archive

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||