|

|

Found - protein that turns off biological clock

A protein associated with many kinds of cancer cells, can suppress the circadian clock running every cell's 24 hour cycle. This result has implications not only for cancer treatment, but for re-working the clock itself.

The ticking of our biological clock, or circadian rhythm, drives all our gene activity, sending protein levels up and down, initiating 24 hour cycles in virtually every aspect of all animal physiology. It is tuned to the daily cycle of light and dark, sending out synchronized signals to molecular clocks in every cell and tissue of our body - except the germ (sperm and egg) cells. Its disruption is associated with diabetes, heart disease, cancer and more.

A new study led by researchers at the University of California Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz) has identified a protein associated with cancerous cells — also turns out to suppress cellular clocks. The discovery, Molecular Cell1, adds to growing evidence of a link between cancer and disrupted circadian rhythms.

"The clock is not always disrupted in cancer cells, but studies show that disrupting circadian rhythms in mice causes tumors to grow faster. One of the things the circadian clock does is set restrictions on when cells can divide."

Carrie Partch PhD, Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry, UC Santa Cruz and corresponding author of the paper.

The new study focused on the protein PASD1. Collaborators at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom, previously found PASD1 in a broad range of cancer cells, including melanoma, lung and breast cancers. PASD1 belongs to a group of proteins known as "cancer/testis antigens" normally found in germ cells which become sperm and eggs.

Cancer researchers have been interested in PASD1 proteins as markers for cancer — and as potential targets for cancer vaccines.

Says Carrie Partch PhD, a professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at UC Santa Cruz, and one of the authors of the paper, "Understanding how PASD1 is regulating the circadian clock could open the door to developing new cancer therapies. We could potentially disrupt it in cancers when it is expressed."

Beyond its role in cancer, Partch is also interested in understanding the normal role for PASD1 — and answer the question "why is the germ line the only tissue in the body that does not have circadian cycles."

Partch's lab has revealed how PASD1 proteins interact with the molecular machinery of the biological clock:

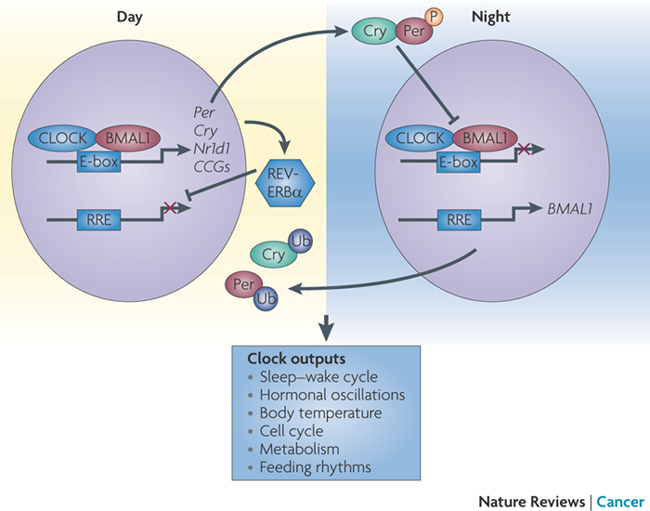

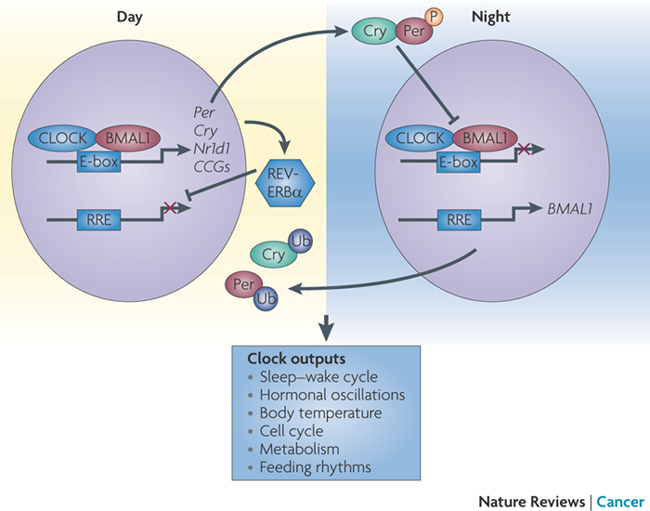

[a] There are four main clock genes. The interactions of these 4 genes and the proteins they encode, create a feedback loop which keeps molecular oscillations on a 24-hour cycle.

[b] Two proteins, CLOCK and BMAL1, form a complex that turns on both the Period and Cryptochrome genes.

[c] The Period and Cryptochrome proteins will then combine to turn off the genes for CLOCK and BMAL1.

[d] PASD1 is structurally related to CLOCK, interferring with the function of the CLOCK-BMAL1 complex.

"It shuts clock off very efficiently," adds Partch. Cancer cell lines that express PASD1 show it can be blocked with RNA interference which turns the clock cycle back on.

Partch's lab is continuing to investigate biochemical mechanisms involved in molecular clocks: "By understanding what makes the clock tick and how it is regulated, we may be able to identify where we can pharmacologically intervene — treating disorders in which the clock is disrupted."

Another recent paper from Partch's lab, published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology2, researchers at UC Santa Cruz and the University of Memphis worked out important details of interactions between the two main clock proteins: Cryptochrome interacts with a particular section of BMAL1. Any mutations that cause structural changes where these two proteins interact, can alter clock timing, cutting cycles to 19 hours or extending the cycle as long as 26 hours.

"This study answers the longstanding question of how Cryptochrome works. If we can control this process using small molecules, we can affect the timing of the clock," Partch said.

Several clock gene mutations have been identified in people with disorders causing either advanced sleep syndrome or delayed sleep syndrome. There is also growing evidence that environmental changes (such as shift work and jet lag) affect circadian rhythms and can have profound effects on human physiology and health.

"There are vast consequences to trying to live outside the natural daily cycle. We know that clock disruption in general is not a good thing, and we have ongoing studies to explore its role in cancer and other human health problems."

Carrie Partch PhD

Abstract 1 Highlights"Cancer/Testis Antigen PASD1 Silences the Circadian Clock," Molecular Cell

• PASD1 is evolutionarily related to the circadian transcription factor subunit CLOCK

• PASD1 is a nuclear protein that inhibits the transcriptional activity of CLOCK:BMAL1

• Regulation of CLOCK:BMAL1 by PASD1 is functionally linked to CLOCK exon 19

• Downregulation of PASD1 improves amplitude of cycling in human cancer cells

Summary

The circadian clock orchestrates global changes in transcriptional regulation on a daily basis via the bHLH-PAS transcription factor CLOCK:BMAL1. Pathways driven by other bHLH-PAS transcription factors have a homologous repressor that modulates activity on a tissue-specific basis, but none have been identified for CLOCK:BMAL1. We show here that the cancer/testis antigen PASD1 fulfills this role to suppress circadian rhythms. PASD1 is evolutionarily related to CLOCK and interacts with the CLOCK:BMAL1 complex to repress transcriptional activation. Expression of PASD1 is restricted to germline tissues in healthy individuals but can be induced in cells of somatic origin upon oncogenic transformation. Reducing PASD1 in human cancer cells significantly increases the amplitude of transcriptional oscillations to generate more robust circadian rhythms. Our results describe a function for a germline-specific protein in regulation of the circadian clock and provide a molecular link from oncogenic transformation to suppression of circadian rhythms.

The first author of the Molecular Cell paper on PASD1 is Alicia Michael, a graduate student in Partch's lab. Other coauthors include Stacy Harvey, Patrick Sammons, and Hema Kopalle at UC Santa Cruz, and Amanda Anderson and Alison Banham at Oxford. This work was supported by grants from the UC Cancer Research Coordinating Committee, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and the U.K. Cancer Research Programme, and a Paul & Anne Irwin Cancer Research Award to Alicia Michael.

Abstract 2: "Cryptochrome 1 regulates the circadian clock through dynamic interactions with the BMAL1 C terminus" - Nature Structural & Molecular Biology

The molecular circadian clock in mammals is generated from transcriptional activation by the bHLH-PAS transcription factor CLOCK–BMAL1 and subsequent repression by PERIOD and CRYPTOCHROME (CRY). The mechanism by which CRYs repress CLOCK–BMAL1 to close the negative feedback loop and generate 24-h timing is not known. Here we show that, in mouse fibroblasts, CRY1 competes for binding with coactivators to the intrinsically unstructured C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) of BMAL1 to establish a functional switch between activation and repression of CLOCK–BMAL1. TAD mutations that alter affinities for co-regulators affect the balance of repression and activation to consequently change the intrinsic circadian period or eliminate cycling altogether. Our results suggest that CRY1 fulfills its role as an essential circadian repressor by sequestering the TAD from coactivators, and they highlight regulation of the BMAL1 TAD as a critical mechanism for establishing circadian timing.

The first authors of the Nature Structural & Molecular Biology paper on Cryptochrome are Chelsea Gustafson, a graduate student in Partch's lab, and Haiyan Xu at the University of Memphis. Other coauthors include Patrick Sammons, Nicole Parsley and Hsiau-Wei (Jack) Lee at UC Santa Cruz, and additional collaborators at the University of Memphis. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Return to top of page

|

|

|

Feb 2, 2016 Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News News Archive

Circadian rhythm is regulated by a gene feedback loop that can be interrupted.

The proteins CLOCK and BMAL1 combine to form a complex that turns on both

the Period and Cryptochrome genes — which then turn off CLOCK and BMAL1.

Image Credit: Nature Reviews

|

|

|

|